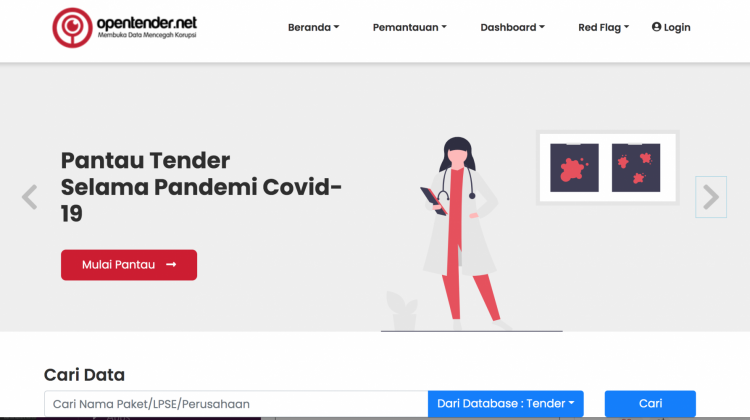

Opentender.net, the site helping Indonesians spot shady government spending

In 2015, Indonesian police arrested two officials and two city councillors in Jakarta over a Rp 330 billion (US$23 million) corruption scheme involving generators supplied to schools across the city. The governor had reported the case to law enforcement agencies after receiving a tip-off from the civil society group Indonesia Corruption Watch (ICW). Researchers at ICW suspected something was wrong after their risk monitoring site opentender.net showed that seven of the ten most risky tenders for the Jakarta province in 2014 were related to the project (commonly known as the UPS case). On further investigation, the data showed generators were purchased at a mark up of 300% on the usual retail price. Authorities followed up with their own probe. Since enforcement of anti-corruption laws in Indonesia is generally poor, ICW saw it as a win that the police took the suspects into their custody. One of the accused, a senior education official for West Jakarta was found guilty of corruption and money laundering. He was sentenced to five years in prison and some of his assets were seized.

The UPS scheme is just one of the corruption cases that have been exposed with the help of the opentender.net platform. Created by ICW with support from the national public procurement agency LKPP, the portal includes easy-to-use analytics tools that allow anyone to look at corruption risks and other indicators associated with public procurement performance, such as competition, efficiency, and value for money.

ICW uses the platform for flagging tenders in need of further investigation (as happened in the UPS case) or for corroborating evidence from other sources. When a whistleblower told ICW about corruption in a national scheme to produce electronic identity cards (E-KTP), they could cross-check the complaint with information in their database, which aggregates procurement data from various official sources and different stages of the contracting process. ICW warned the minister in charge at the planning stage, Home Affairs Minister Gamawan Fauzi, but the ID card deal went ahead. The authorities’ subsequent investigation into the case implicated dozens of top legislators and bureaucrats and estimated the cost to the state at Rp 2.3 trillion (over US$161 million). In 2017, the Speaker of the House (Ketua DPR) Setya Novanto was sentenced to 16 years in prison. During his trial, Novanto named other ministers who allegedly profited from the scheme, including Minister Fauzi who has denied the claim. The Corruption Eradication Commission’s investigations are ongoing.

More recently, ICW has been scrutinizing procurement of medical equipment to curb the pandemic. They identified deals that were awarded to companies without previous experience, using data published on opentender.net to check the suppliers’ track record in procurement. Using data from other sources, they also found 14% of contracts awarded through the direct procurement method exceeded the maximum amount allowed for this method. The central government had only distributed a fraction of the personal protective equipment (PPE) needed by health workers treating COVID-19 patients. And finally, medical equipment wasn’t being distributed to the provinces with the highest number of positive cases either.

A new version of opentender.net was launched in April 2021, with a host of new features and structured data published in internationally recognized open contracting data formats.

Opentender.net version 3.1 has now also a wider range of red flag indicators to detect risks and inefficiencies with greater accuracy.

Original red flag indicators - New red flag indicators

Contract value - Days between tender announcement and signing of contract

Value for money - Number of characters in tender title

Timing of tender announcement - Number of characters in tender description

Repeat winner

Number of bids (removed in version 3.1, source data no longer available)

New dashboards allow users to monitor three major categories of procurement spending: national contracts, those related to the COVID-19 pandemic, and infrastructure. On each dashboard, users can view particular trends, such as the monthly volume and value of procurement, competition, internal efficiency, integrity and value for money.

The platform also includes a new dataset for transactions conducted using the e-purchasing method (used for goods, works and services listed in the e-catalogue).

For researchers and other users who might want to do more sophisticated data analysis, the platform features data structured in the Open Contracting Data Standard (OCDS) format. This allows anyone to access data from over 500 local governments and national agencies, different platforms and different stages of the contracting process easily in the one place.

Data on the different stages of the contracting process are scattered across more than seven source websites. Opentender.net brings them all together in one standardized format.

ICW is now working to create red flag indicators for a new dataset on non-competitive procedures (direct announcements and direct appointments), along with other improvements to the data, analytics and integrated feedback loops to make it even easier to monitor public procurement.

ICW’s procurement monitoring efforts have come a long way since 2010, when they first released research on corruption risks in government contracts as an Excel spreadsheet, using data that ICW had scraped manually from the government’s electronic procurement system. In 2012, ICW started presenting its findings to LKPP and the two organizations began collaborating, launching the Opentender platform in 2013.

Now ICW and LKPP mentor local civil society groups and journalists to conduct their own investigations into irregularities at the sub-national level. One such collaboration involved reporters and civil society researchers from the Yogyakarta province.

Cooperating allows these groups to complement each others’ strengths. The civil society organization has the access and time to successfully obtain budget data and other details, while the journalists can report the findings to a larger audience. After sparking a public debate, the civil society group can approach the government with more in-depth recommendations for reform. This approach helped to expose problems in a project to build a trade center for street vendors in Malioboro. The contract was awarded through a fast-tracked procurement method that was only supposed to be used for small projects. The investigation also revealed that suppliers for two of the three construction deals were controlled by one person, which hinted at possible collusion. The local government publicly admitted the tender violated the rules, and although the investigation team couldn’t definitively prove there was corruption in the project, they may have just prevented similar schemes from occurring in the future.

Published in the Open Contracting Partnership Blog, 19 Jul 2021

by Sophie Brown