Annual Report ICW 2019

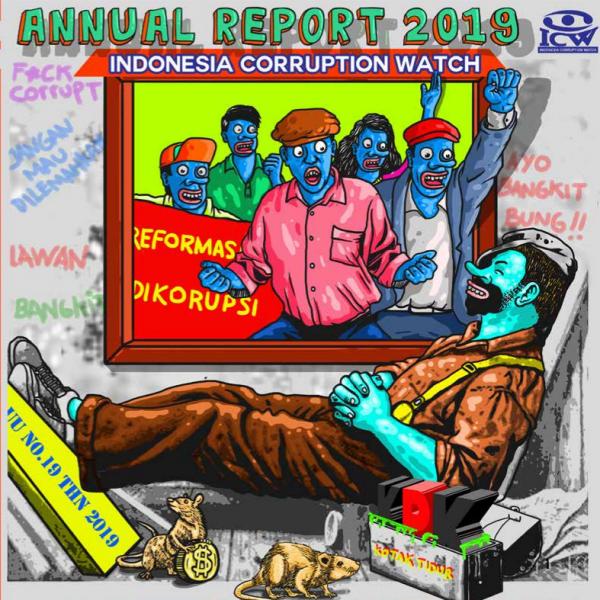

2019 was an extremely difficult year for corruption eradication. Although many believed Indonesia had a good person as President and the community was much more hopeful that corruption eradication would be far more thorough under Jokowi, the reality fell short of expectations. The fact was that under Jokowi the fight against corruption was, if anything, under assault. Law No. 19/2019 on the Corruption Eradication Commission (known as KPK), revising the existing Law No. 30/2002, was adopted by acclamation. Claims by the Palace and Parliament that the motivation for the change was to strengthen the law was simply a smokescreen, because fundamentally the new law only served to weaken efforts to eradicate corruption.

Civil society’s efforts to thwart plans to revise the KPK law came to nothing, despite the sacrifice of four student lives and the injury (both serious and minor) of hundreds of others in the most widespread student protests since 1998. The government was unmoved and the KPK bill sailed through. The direction of national policies, effectively ignoring reformist agendas, inter alia, on settlement of historic cases of serious human rights abuse, corruption eradication and the rule of law was the opposite of the views of some voters who thought Jokowi was a person of quality. In a reaction to government policies which reflected people’s eagerness for reform, a new civil society coalition emerged under the banner #ReformasiDiKorupsi (Reform being Corrupted)

In such a situation, civil society including Indonesia Corruption Watch (ICW) had to start thinking outside the box about how to promote reform agendas without relying any longer on the government or the KPK. Factors contributing to this situation were: the government had already taken the side of the wealthy and investors; the KPK’s authority had been whittled away by the new KPK law; and the newly appointed KPK leadership did not exhibit qualities of integrity and professionalism. All of this posed enormous challenges which nonetheless had to be appropriately met.

Although it was becoming ever clearer that the fight against corruption faced a bleak future, the campaign was not entirely without its successes. The Constitutional Court ruled in favour of a referral by ICW and anti-corruption campaign partners seeking to prevent persons formerly convicted of corruption from standing as candidates in local heads of government elections. That meant that, in accordance with the Court’s ruling, such persons could no longer contest local heads of government elections without first waiting out five years of ineligibility. This outcome was one small victory in ICW’s unrelenting anti-corruption advocacy work.

As for the future, an important step forward will be development of a wider coalition of civil society groups who feel disadvantaged by government policies. Campuses and their academics continue to display sound ways of thinking and are in an ideal position to question government policies they regard as encouraging corruption. Moreover, in the regions, the appearance of a cohort of local government leaders who prioritize their communities’ interests and improved public services could develop into a broader network for maintaining optimism about reform.

At the same time educational work aimed at creating a shared public awareness of corruption and its consequences has to be stepped up. The issue is that a mature democracy needs rational voters. Fostering anti-corruption awareness is part and parcel of developing a critical electorate less easily duped by the glib talk of politicians and their sacks of rice, cash hand-outs and instant noodles which are rolled out at every election.